|

|

|

MIM

GREEN

aka

Miriam

Dimondstein

1920-2007

Artist,

Writer,

Puppeteer

|

edited

by Phillis Gershator

|

Mimi, as I

called her, when I wasn’t calling

her Mom, was born to Russian

immigrant parents in 1920. Her

mother, Fanya, was a skilled

seamstress, her father a less than

skilled carpenter (though he later

established a successful lumber

business). The marriage failed, and

Fanya, with her

daughters Miriam and Frieda, moved to the

Lower East Side.

|

|

From

left: Fanya, Frieda, Mimi.

|

|

Leaving

sweatshops and piece work behind, Fanya

worked at home, in her apartment on

Second Ave., as a private dressmaker.

She also shared the apartment with

boarders to pay the rent. One of them,

a shoemaker with two daughters, was to

become her lifelong partner.

|

“Fanya the

Pinsticker,” 1947.

Serigraph.

Mimi’s memory of Fanya

sewing for a

particularly obnoxious

client.

This print

appeared in an juried

exhibition at the LA

County Museum in 1948.

|

Mimi first studied art at

Washington Irving High School in NYC,

where she hoped to enter the

“lucrative” field of fashion art. It's

possible these samples helped

fill out her portfolio when she went

job hunting:

In the late Thirties and early

Forties, Mimi took classes in drawing,

printmaking, and painting at the Art

Students League and at the American

Artists School, studying with Nahum

Tschacbasov, Anton Refregier, and

Anthony Velonis. She worked as an

artists model to pay her school fees.

In 2006, when I asked her about her

modeling experiences, she sent me this

email:

|

The

Arts Students League’s pay

at 50 cents

was

the lowest rate allowed by

my union, Local 60 of

the

United Professional and

Office Workers,

C.I.O. I

got a

dollar an hour posing in a

studio rented by

three

French sculptors and also

from Willian Zorach,

who

only copied my feet, so I

asked him why I had to

get

naked. He laughed and said

a nude model made him

feel

like he was young, a

student and back in art

school.

Several

evening sketch groups in

private homes paid 75

cents

an hour and The American

Artists’ School gave me

a

dollar an hour credit

towards my tuition. What I

learned

from Anthony Velonis,

Anton Refregier and

William

Gropper was worth a lot

more than that!

An

amusing, touching,

autobiographical short story

she wrote in 1957 reflects

on her experience:

|

Mimi

clipped this photo

for

modesty's sake.

|

|

THE DISARMED VENUS

Time: July, 1936.

Subject: Me, girl graduate,

one of the two hundred odd

High School art Course

diploma holders who had

spent the last three years

singing, along with some

eleven thousand other

inmates, “Good morning, Mr.

Za-brisk-eee, a Washington

Irving Goil am I, oy, oy,

oy!”

Ah! My alma mater. That

venerable, cherished, noble,

all female institution was

situated catercorner to the

somewhat less venerable

Irving Burlesque, wherein

whose hallowed halls Miss

Gypsy Rose Lee daily

exhibited her talents. But

every day as I passed to and

from the stripper’s theater,

I suffered enough shame and

dishonor to compensate all

womankind for the

transgressions of the misled

Miss Lee.

Forty blocks further uptown

stood another venerable

structure, The American

Artists League, far from the

social realities of the

Lower East Side, but also

stacked with great

traditions, and impregnated

with the odors of varnish,

linseed oil, turpentine, and

thickly coated with the dust

of high grade French

pastels.

There was I, unleashed in

June upon one of the leading

cultural production centers

of the world, armed with a

loaded portfolio and imbued

with a strong desire to

delve into the deeper

mysteries of Fine Art. (At

least until job hunting time

in September.)

The problem? Money for

tuition, lack of.

Solution? I filed a request

for a work scholarship, and

then sweated out the days

before the summer session.

When the interview was

granted, there was only a

cursory glance at my

carefully chosen samples.

The questioners were seeking

information about my

physical properties, and I

suffered some prolonged,

pertinent inspection of my

person. But--the board

awarded me a scholarship!

Floating on an airship of Da

Vinci design, I came to the

conclusion that talent,

ability, and sincerity win

out over poverty every time.

Alas, the three virtues had

nothing to do with it. As

the registrar gave me a slip

explaining the nature of my

scholarship, I fell from

space with a flop. My simple

duties, in exchange for the

best available afternoon art

course: ”Pose in the nude,

Rofarge figure sketching

class, 9 to 12 A.M. Room

3A.”

There was a serious

professional model shortage

in the metropolitan area

every July and August. Most

artist’s models, Local 60,

United Office and

Professional Workers of

America, C.I.O., had the

sense and resources to

escape New York City’s heat

and humidity. Since

employment was available

elsewhere, off they would go

to gainfully disrobe in the

pleasant little summer art

colonies of Woodstock and

the New England Coast,

leaving New York City

without figure models,

except for unsophisticated

novices like me.

My first disrobement, before

fifteen friends, strangers,

and fellow students, mostly

fellows, was a troubled,

trembled, never to be

forgotten time of

affliction. I blushed,

perspired, swallowed,

searched frantically for my

hands and feet and a place

to put them, when relief of

a temporary sort came with

the idea that a Martha

Graham type pose would have

such abstract interest, it

would surely negate the

terribly naked reality. So I

struck it.

The students were very kind.

Embarrassed for me. Quiet.

They watched me twist into a

grotesque swastika that even

Hercules couldn’t have held

for twenty, let alone ten,

minutes.

Another scholarship student

and friend, Dave, the class

monitor, looked at his watch

and lost his voice. A few

energetic enthusiasts

rustled their newsprint to a

clean page and started fast,

convinced I couldn’t

possibly last five minutes.

The serious anatomists

worried the charcoal between

indecisive fingers when

Monsieur Rofrage walked in,

stared at me, and loudly

challenged, “WHAT ARE YOU

DOING WITH YOUR BODY?” Dave

whispered that since this

was a first pose, and indeed

my first time as a model, he

had not interfered with my

choice.

“NONSENSE.” But after

considering a moment,

Monsieur softened, and the

French lilt of his voice

dissolved the heavy air.

“Break the pose and rest!

Attention, class. We’ll work

for line, pure pen and

pencil line. No charcoal,

chalk or shading. Ten minute

poses, simple standing poses

for contour and quiet

movement, and PLEASE, design

the PAGE.”

He came to the model stand

and spoke quietly. “Relax

your poses. We want to enjoy

the natural grace of the

human female form. We may

take on the muscles later,

and their varied

manipulations, but for now,

be Venus on the the half

shell, or any of the Three

Graces, just, perhaps,

standing with weight so,

lightly, on one leg.” And he

assumed a stance. I broke

into giggles, tension

released, like a brook

suddenly free of stones. He

looked so funny posing on

the half shell, and he spoke

so sweetly, and he was,

after all, the dearest,

finest, best of all possible

artists, teachers, friends.

I would cheerfully die for

him, contort myself into

knots, half Nelsons, and

double hitches, and all he

asked was an easy pose which

my restless, miserable,

nervous body could surely

hold for FORTY-FIVE minutes,

French model style.

Within ten minutes, sweat

was trickling down between

my arms and sides, and I WAS

dying. My neck was sore, the

muscles aching, the nose

itching, the right ear

twitching, and one leg about

to give way along with my

whole crumbling future. When

Oh! Blessed King David

signaled and called out the

magic word that releases

fair maidens from stone

statue witchery. There is no

more beautiful word in the

English language, none with

a more poetic, ringing

sound, nor half the potency

and meaning. “CHANGE!”

So it went for three long

hours, with five minutes off

every twenty-five, and a

fast fifteen minute break

somewhere in between the

time that didn’t move. But

in that agonizing three

hours there was a quiet

growing. I think I caught a

glimpse of what the Yogi

knows, a satisfaction in the

disciplined control of mind

and body. A model has the

further satisfaction of

knowing how to look at those

who look so piercingly at

her, searching, trying to

learn from her. It was a

good relationship, and there

was nothing immoral about

it. How foolish to have

harbored shame! After all,

what is a body? A source of

education, certainly, and a

source of life. This was a

LIFE CLASS. A class in LIFE.

Dave called the final

“REST.” Oh, the sweet

deliverance! I donned street

clothes in the undressing

room, bounced down three

steps at a time, and strode

through Central Park, a free

and mobile soul. Having

stretched, run, and breathed

deeply, I stopped to sketch

a solitary tree, marveling

at the growth pattern of

trunk into limbs into

branches, then

rejoiced--because the model

wasn’t me!

|

Mimi

joined the Youth Workshop in

the Thirties and traveled with

a group of talented folk in

1939, puppeteering in

Wisconsin and Michigan. She

told me about living on Jane

Street in the West Village in

those prewar days, and running

a soup kitchen to help pay the

rent. Curator Judith E. Stein

describes the times in an

article about the artist Jacob

Landau:

In the late thirties and

early forties, New York was

a crossroads of leftist

culture, bringing together

artists who were passionate

about the labor movement and

politics in general. Landau

was one of the founders of

the Youth Workshop in 1939,

which counted as members

puppeteers, musicians,

actors, and such graphic

artists as Leonard Baskin

and Antonio Frasconi. They

were united by the common

goal of bringing art to the

"people." Ever short of

funds, the Workshop would

host monthly "rent parties,"

where such talented young

people as Zero Mostel, Woody

Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Will

Geer, Canada Lee, and

Leadbelly would offer

entertainment.”

Zuni Maud and Yosl Cutler’s

“incomparable puppets” also

influenced Mimi, with their

performances on the Lower East

Side and in North Branch at a

summer place called "Maud’s

Summer-Ray."

When I mentioned coming across

the familiar names Maud,

Cutler, and Maud's Summer-Ray

in a magazine, she wrote back:

|

Dear Phillis,

You stirred a bunch of

memories. Zuni Maud and Yosl

Cutler painted murals in the

main and children’s dining

rooms that are still vivid

in my imagination. I got to

study them breakfast, lunch

and dinner. They were

clever, vibrant, satirical,

joyous, irreverent and rich

in symbolism. …Until now I

didn’t realize how much I

was influenced by their

work. Those two guys were

multi-talented geniuses in

puppetry and artwork. They

wrote plays, poetry, songs

and comedy... They put

together costumes. They did

opera spoofs way before Sid

Caesar’s T.V. Show of

Shows.

The Modicuts [puppets of the

Modicut Puppet Theater]

included a variety of

puppets and marionettes that

entertained us on summer

evenings with hilarious

skits and dances. Zuni Maud

taught me to play chess when

I was about eight.

[Note from Phillis--he must

have been a good teacher

because Mimi was a

formidable chess player.

Certain men didn’t like

playing chess with her

because they couldn’t handle

losing to a women!] |

Puppetry

became a passion Mimi

returned to when she wrote

scripts for the Lou Bunin

Puppets and, many years

later, when she used

puppetry in Ringwood, NJ, as

a teaching and therapeutic

tool.

|

|

|

|

Ballerina

sock puppet

or, in a pinch, a

Princess.

|

Madame

Cacciatore

(Chicken of the Opera)

and various other

hen-ish

characters.

|

Ghostly

spirit

manipulated

with sock and strings.

|

“Shy

persons,” she wrote in the

1980’s, “can freely express

themselves with puppets, and

puppets can delight even a

depressed or hostile

audience. At the Passaic

County Adult Day Care

Center, an embittered

gentleman in a wheelchair

refused to participate in

after-lunch activities in

the craft room. Fairy

Grandmother Pippette

fluttered toward him on mesh

onion bag wings guided by an

almost invisible discarded

guitar string. Claiming an

ability to grant even

unexpressed desires, she

offered him three wishes. He

looked up but wouldn’t talk

to the puppet, so she

scolded: 'Shame on you! Why

don’t you give me a chance

to prove my worth? Take your

time and think hard about

what you really want, but

don’t be impulsive.

Remember, whatever you wish

can come true. Are you ready

to wish? Do you know for

sure what you absolutely,

really want? OOOPS, too

late! I have to catch my

bus. Goodbye!' Flutter,

flutter. With a sideways

look, the elderly gent made

a halfhearted gesture of

dismissal. 'Get away from

here. You make me laugh!'"

|

|

|

Chopstick

bird puppets

made of REAL, if

scraggly,

feathers,

thread-spool thighs,

and various other trash

treasures.

|

Evil

Prime Minister Haman,

from Mimi's retelling of

the Purim

story, which included a

bevy of

bead bedecked belly

dancers.

|

In

the Forties, Mimi received a

lithography scholarship from

Lawrence Barrett at the Fine

Arts Center in Colorado

Springs. Later, in

California, she worked with

printmaker Lynton Kistler.

|

"Scorched

earth," 1943. Lithograph.

|

"Sedition,"

1947. Lithograph.

Selected for Library of

Congress

National Print Exhibition,

1949.

|

In

1942, Mimi married Morton

Dimondstein, fellow artists

and activist. She followed

him to Colorado Springs

during the war, and to Camp

Adair in Oregon before he

was shipped overseas with

the 104th Infantry Division.

One art project they

collaborated on was a mural

for an artillery division

officers’ club in Colorado.

It no longer exists, but

here's the design sketch:

Mimi also painted a mural

for the USO Kosher Kitchen

in Colorado Springs and

murals for the non-com and

officer clubs at Camp Adair.

I found one of her sketches

for "Three Day Pass," part

of a narrative sequence,

which included a brief, less

than three day, romance:

|

Mimi

moved to Los Angeles to

work. She described her job

to Suburban Trends,

a NJ newspaper (June 8,

1986): “During the war I

worked on airplane

recognition films for the

army. We created animated

films that showed plane

silhouettes so the artillery

would be able to tell whose

planes were passing

overhead, so they wouldn’t

shoot down our planes....”

She also created war related

murals at various sites.

“The murals I did for a

school in LA were

destroyed,” she wrote in an

email in 2006. “The panels I

recall are an African

American woman as Liberty

leading the multinational

people and another of an

integrated group of men and

women architects and

engineers designing the

reconstruction of the world.

|

"William

Gropper came to

L.A.,

saw

me at work and

remembered

me

as a student in

the American

Artists’School.

He approved and

beamed

paternally.

"A year later, during

the post war era,

the school

was

converted

to

an air

force

academy and the

walls were

repainted."

|

This

lithograph for

D-Day, "June 6,

1944" (above),

reveals

Gropper's

influence on

Mimi's work.

So does

the sketch to

the right.

Warmongers and

profiteering

types populate

many of her

cartoons

and political

paintings.

|

|

After the war, Mimi, Morton,

and Manny Singer opened a

frame shop and gallery in LA

where they sold affordable,

original serigraphs

(silkscreen prints). Mimi

also worked in advertising

and created greeting cards,

in addition to designing and

executing post-war public

and private murals.

|

|

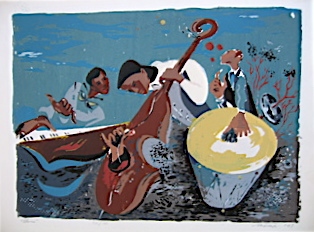

"Blues,"

1947. Silkscreen

print.

|

"Hootenany,"

1947. Silkscreen

print.

Pete Seeger,

Sonny Terry, and

Bess Lomax

Hawes.

|

"I was a member of the

screen cartoonists guild for

ten years" in the Forties

and early Fifties, Mimi told

the Suburban Trends,

a NJ newspaper. “In

Hollywood, at the guild, we

were trying to get away from

violence and sex and get

more into

education....” To that

end, she apprenticed with

Graphic Films, did free

lance for TV Spots and Fine

Arts Products, and assisted

Ed Levitt on limited

animation, a technique he

used in the first Charlie

Brown/Peanuts TV

productions.

Mimi wrote

several

autobiographical

poems/ballads.

This one, written in

1979, addresses the

job situation for

woman pre and

post-war:

JOB MARKET

Time was

1936. Place, a city

like New York.

Player is

an art school grad

looking everywhere

for work.

Every art

school student

reaches for the

perfect job to be.

And the

teacher tells us

each is rich in

opportunity.

Then we go

out to the market

and the bubble

disappears

with the

voice of art

directors ringing

loudly in our ears:

“Art is not

the way to go

for a

woman, don’t you

know?

She can sew

and wash the dishes

or

perpetuate the

species.”

I made

lists of every kind

of art work

possibility

from the

yellow pages of the

telephone directory,

wrote my

hopeful letters to a

hundred companies,

clipped the

want-ads and applied

to advertising

agencies.

“Art is not

the way to go

for a

woman, don’t you

know?

She can sew

and wash the dishes

or

perpetuate the

species.”

I pinned my

hair into a bun to

up my age and

dignity.

I walked to

interviews (a nickle

meant a lot to me!).

I applied,

was registered with

every placement

agency,

displayed

my folio to people

who said they’d find

some work for me.

Tried

display and greeting

card, towel design

and children’s toys.

Personnel

was firm and hard:

“We only hire boys.

Art is not

the way to go

for a

woman, don’t you

know?

She can sew

and wash the dishes

or

perpetuate the

species.”

So I wrote

to Mr. Disney,

“California, here I

come!”

And he

answered with a

letter, “East coast

woman, stay at home.

Men are

trained for

animation,

background art and

in-between.

Girls work

here to ink the

cells before they go

onto the screen.

Art is not

the way to go

for a

woman, don’t you

know?

She can sew

and wash the dishes

or

perpetuate the

species.”

Then the

country went to war

and the men in

animation

were all

drafted to make

films that would

help defend the

nation.

Mary Blair

did Disney stories,

and Bernice did

backgrounds for

Warner

Brothers cartoon

features when the

men went off to war.

I did

airplane

recognition,

storyboards and

in-between.

Sterling

Sturtevant was art

director for the

cartoon screen.

Art became

the way to go

for a

woman, don’t you

know?

She could

even work for money

drawing

sequels to Bugs

Bunny!

When we

helped the world

defeat the Fascist

and the Nazi hordes,

G.I.’s came

back to work and

women lost their

storyboards.

We returned

to ink and paint or

out to hunt for work

again

and apply

for better jobs,

just to hear the old

refrain:

“Art is not

the way to go

for a

woman, don’t you

know?

She can sew

and wash the dishes

or

perpetuate the

species.”

She can

breed a little

soldier or another

little breeder

and be glad

she can depend upon

a working man to

feed her.

Now the men

who run the show

tell our children

what to be,

tell them,

“Off to war you go

to protect

democracy!”

And they

build their deadly

weapons with the

taxes that we pay.

Equal

Rights becomes a

slogan for a country

far away.

“Peace is

not the way to go

for a

woman, don’t you

know?

Be a

soldier-bearing

mother

and

exterminate each

other!”

Men who

make rules own women

who will eagerly

assist ‘em,

and they

also own the media

that sugar coats the

system,

but with

songs and art to

teach us, we can

help expose the

leeches

and

together with our

brothers we can

liberate the

species!

The poor job market,

divorce and

remarriage, three

daughters, a move back

to the east coast, and

another divorce and

remarriage slowed but

didn’t stop her

creative output. She

continued to create

artwork in a variety

of genres and styles.

She had a special gift

for seascapes and

animals, and was

inspired to combine

both in several

metamorphic "sea"

horse paintings (an

example on the left):

And she continued to

write stories, novels,

plays, poetry, songs.

To develop her skills,

she took courses in

writing for television

with Walter Hartman at

Brooklyn College,

musical theater with

Aaron Frankel at the

New School for Social

Research, and

playwriting with Jan

Hartman at the

Circle-in-the-Square

Theater School. Her

song lyrics reflected

a love of language and

rhyme. At times she

liked to "improve" on

classics, revising

them or adding her own

verses. Her addition

to "Amazing Grace,"

for example, can be

found in the Folk

Process column of Sing Out

magazine, Volume 64, #

4, pages 54/55.

It was a real

privilege having such

a creative mom, who

could make

personalized paper

dolls for us, board

games like “Fate” and

“Big Game,” and

birthday cards

listing, in rhyme, our

accomplishments. She

influenced,

encouraged, and

inspired our own

creativity, too. When

I started writing

books for children,

Mimi became my

sounding board--and

often my collaborator.

One of the stories we

wrote together, a

bedtime book for

preschoolers titled Who’s

Awake in

Springtime?

(Holt), is

delightfully

illustrated by the

talented French

artist, Emilie

Chollat, and was a

children's

book-of-the-month club

selection for February

2010. She did the

illustrations for The

Fisherman's Horn

(Campana), which I

completed. Another

young picture book we

had collaborated on, Time for a Hug

(Sterling),

with

adorable

illustrations

by David Walker, came

out in January 2012,

in time for National

Hug Day!

|

Here's a

photo of Mimi

as a gypsy at

an event in

NJ, reading

fortunes for a

good cause no

doubt. A

corner of the

board game

"Fate," which

she devised,

is visible.

Actually, she

found she was

so accurate at

palm reading,

it gave her

the willies,

and she gave

up readings

forever. It

wasn't the

palms so much,

although a

worn or even

smooth hand

can reveal a

lot, it was

the expression

in the

eyes,

mouth....

A

selection of

game card

designs for

"Fate":

|

|

|

Mimi was observant. As

a portrait painter she

had to be. She was

exceptionally good at

the quick and telling

sketch. She did five

minute, ten minute,

thirty minute sketches

at fairs. Watching

artists plying that

skill in a NYC park

recently made me think

of the hundreds of

sketches she gave away

and sold, not to

mention all the

sketches of musicians

she did when she went

to music festivals and

concerts, and of

community activists

when she went to

meetings. She did

sketches (for

publication) of

attendees at the

historic San Francisco

conference in 1945, a

series in the 1980's

of illustrious women

such as Margaret

Sanger, and of course,

many sketches of

family members

throughout the years.

Here, from left to

right, are sketches of

Mimi's mother in 1956,

a self portrait in

1947, and Mimi's first

born in 1942.

She worked most often

in pen and ink,

watercolor, oil, and

acrylic. When she

visited Italy in 1984,

she returned to

printmaking, building

on her earlier success

as a young

lithographer. She

produced a number of

lithos in Florence,

which were drawn on

Bavarian limestone and

printed by Tamara and

Raffaello Becattini of

Edi Grafica Printers.

In a postcard she

wrote, “I am on a roll

creatively. After

years of somnolence,

the stuff is busting

out!” She also worked

on stone at another

prestigious studio, in

Milan, and was very,

very excited about the

piece, but the stone

was completely

destroyed (on account

of its political

content she

suspected), and though

she was offered a

replacement stone, she

lost, for a time, her

high spirits and

momentum.

|

|

“Coup,”

1984.

Lithograph

which received

first prize in

graphics at

the Ringwood

Manor

Arts

Association

19th Annual

Exhibition. |

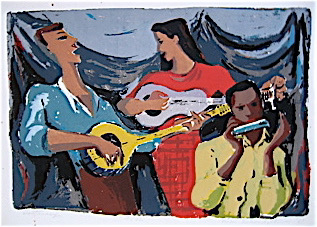

"Three

Musicians,"

1984.

Lithograph

conceived as a

memorial

to her late

husband, Sol

Green, with

whom she

enjoyed

countless

concerts.

|

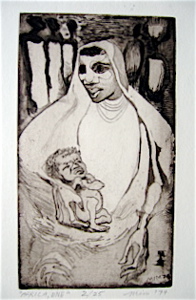

She also tried

her hand at

another

graphic

technique,

etching, but

the themes she

approached

were so

painful, one

influenced by

Kathe Kollwitz

and others by

the news of

famine in

Africa and the

coup in Chile,

that she found

she was

unconsciously

grinding her

teeth to bits. |

|

After that, as she

told her oldest

granddaughter, she was

ready to turn to

flowers--

cheerful florals in

watercolor.

Mimi was

enthusiastically

involved in so many

things! A passionate

gardener who loved to

study seed catalogs

and plants, especially

herbs and their

healthful properties;

a great cook who

invented her own

recipes, taking Adele

Davis to heart early

on; an

environmentalist and

recycler who served,

for example, on the

Borough Conservation

Commission in

Ringwood, NJ, and

chaired the local

League of Women Voters

environmental quality

committee; an active

demonstrator, petition

signer, check signer,

and

letter-to-the-editor

writer when it came to

social justice and

progressive causes;

and a teacher, on both

the east and west

coast, from her

teenage years on into

her 70’s, of art,

puppetry, and dance in

schools, summer camps,

and senior centers.

Yes, dance, too, on

top of everything

else! In her youth,

Mimi studied dance for

over a dozen years

with such teachers as

Alyse Bentley, Pauline

Koner, Nadia

Chilkosky, and

Gertrude Knight.

I still remember the

dance classes she

conducted in

California--we

children were seeds.

We sprouted, we grew,

our branches reached

up to the sun.... We

were also the wind,

rain, snow.... I was

reminded by an old

family friend that, in

our post-war San

Fernando Valley tract

house, we didn’t have

much furniture in the

living room, but we

did have a ballet bar.

Mimi’s publications

include artwork and

articles in the NJ

magazine “Talking

Wood,” co-authorship

of Who’s Awake in

Springtime?

(Holt) and Time

for a Hug

(Sterling),

illustrations for Honi’s

Circle of Trees (Jewish

Publications Society), I See

America Dancing

(Aries Acres, IA), Between Day

and Night (in

Yiddish, Harlick

Press, LA), Elegy for

Val and Bang Bang

Lulu (both

X-Press Press, NY), The Fisherman's Horn (Campana), The

Big Roar (Campana),

and greeting cards for

Brownies Blockprints

(NY) and Fraymart

Gallery (CA), in

addition to her

lithographs, etchings,

and silkscreen prints.

|

|

|

Silkscreen

print

greeting cards

from the mid

1940's.

|

She exhibited her work

under her mother’s

abbreviated maiden

name, Login, and her

own married names:

Dimondstein, Cohen,

and Green, until

she finally signed

herself, simply, MIM.

Her artwork can be

found in private and

public collections and

has been exhibited in

“one man” and group

shows at, among

others, the Library of

Congress National

Print Show, Brooklyn

Museum National Print

Show, Raymond and

Raymond Galleries

(CA), Fraymart Gallery

(CA), Institute of

Modern Art (CA),

Ringwood Manor (NJ),

Valley Center for the

Arts (CA), Ringwood

Public Library (NJ),

Oakland Art Show (NJ),

First Unitarian Church

(CA), LA County Museum

Print Show, Salem USO

(OR), Irving Savings

and Loan Association

(NJ), New Jersey “Fall

Open” Print Division,

and Island Galleries,

St. Thomas

(USVI).

Mimi was always a

great letter writer,

sharing news about her

garden, books she’d

been reading, current

events, meals and

recipes. She always

added a few newspaper

clippings and cartoons

with her letters, and

she freely and

frequently dispensed

her philosophy of

life, in which JOY

played a big part. In

1943, she wrote to her

mother: “In only one

way could my love and

respect and pride in

you be made any

deeper. And more

important, this one

way would make you

healthier, happier,

and give you a greater

joy out of a longer

life. It is to stop

worrying needlessly.”

“I want you to enjoy

life, so please forgo

anxiety,” she wrote me

forty four years

later. “Do it to make

me happier. I know it

will be a wrench to

part with worry, but

you must give it a

shot. Think of all the

positive, creative

things you can put

into a mind when you

put out the

negatives.”

In one missive, she

spelled out her wishes

for a memorial, which

her daughters

attempted to carry out

to the letter when the

time came (including a

good approximation of

the ample and detailed

menu she suggested):

“My wishes in the

matter of my

departure: get

together to tell funny

stories about me and

to remember all the

good times. Eat well

and play my favorite

music. Dance. Do NOT

make speeches but you

might read a poem or

two. Enjoy each other.

Sing. Play guitars.”

In

future,

we will add more of

Mimi's poetry and

prose to these pages,

plus examples from her

hundreds of cartoons

on love, music, dance,

food, law, war.... We

welcome input from

friends and family,

too.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|